Raqs Media Collective: ‘We have been questioning the boundaries of knowledge and art’

Written by Vandana Kalra

| New Delhi |

August 23, 2020 7:00:30 am

The Collective’s trio – (from left) Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula

The Collective’s trio – (from left) Jeebesh Bagchi, Monica Narula

and Shuddhabrata Sengupta. (Tanaka Yuichiro/Courtesy: Organising Committee for Yokohama Triennale)

The Yokohama Triennale is one of the first major art events to take place after a spate of cancellations due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In the curatorial note you mention how “Afterglow” (the title) “lights up an awareness of what it means to keep making art in the twenty-first century”. If you could please elaborate.

The Yokohama Triennale 2020 opened on July 17, with every precaution in place, and with protocols for how visitors can be within the exhibition so as to minimise chances of contact. The opening signals to the world that art is there — to think with everyone in this moment, to invite all to activate the imagination, and to be with thought, desire, and insight into care and contagion.

The Yokohama Triennale Committee, along with us (Artistic Directors) and the curatorial and production teams, had arrived at an understanding that it was possible to install the exhibition and keep it open. It is also our understanding that, almost a decade ago, the Yokohama Triennale 2011, which had opened after the tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear accident, had had an increased turnout. People had turned to art as a source of renewal and solidarity. This time too feels connected to something deeper. It has only been a week since the exhibition has opened, but the initial response from the public, press, and artists to the Triennale has been extremely heart-warming and exhilarating.

In November 2019, we had released a book called the Sourcebook, both in print and also online, and free to download. These were five curated texts, and one extended essay written by us. These sources were the axes shaping our thinking and conversations with artists and the YT team. The realms of luminosity, toxicity, and care —that we laid out in the Sourcebook through texts by different authors from different places and different times—were central to the way in which we were laying out our thinking for the Triennale, and these concepts had already been active amongst us for some time before that. When we met artists in the process of building the Triennale, these axes were deepened. The artist Masaru Iwai, for instance, has been working in post-Fukushima cleaning operations, as an artist-worker for many years. For YT2020 he evolved a networked performance Broom Stars, which is both online and offline, in the public and domestic spaces of the city, and in the exhibition space. This work evolved much before the pandemic, but since then has taken on additional resonance to do with a public thinking of what it means to clean, and focussing attention on those who are the cleaners. Naeem Mohaiemen’s fiction film, made for “Afterglow”, is set in a desolate hospital, and is about a duration of care and its intimacies and impossibilities. The shooting for it was done before COVID-19, but now the film has become a specificity that speaks to a new universal. Artist Renuka Rajiv from Bangalore intensified their work specifically in response to the pandemic, producing a vivid oneiric image-world.

We have all been surprised at how prescient the exhibition has turned out to be. Perhaps that tells us something about the premonitory abilities of contemporary art, and its capacity to tap into the pulse of a time, intuitively.

How would you define the role of the material in the sourcebook?

There is a work in the exhibition — of prints of the moon’s surfaces by the nineteenth century Scottish engineer and inventor, James Nasmyth (along with his observations of folds in the skin of hands and of decaying fruit). These sketches are actually from models of the moon that he had constructed to approximate his and others’ observation of the various moods of the moon. Amazingly, they look remarkably like what we know today the moon is, with all its craters and mounds. Together, they constitute an ‘atlas of the moon’ composed much before such a photographic exercise could be undertaken.

Our Sourcebook is a similar kind of atlas. It points out promontories and scale-elevations that help us make sense of the cartographic affect-image of our present time, as well as provide it a conceptual compass. It helps us, and the artists in the Triennale, navigate a way towards an elaboration of inter-connected complexities and encounters, and an exploration of uncharted perimeters of the personal.

We do consider the Sourcebook, in its non-rivalrous arrangement of different modes of thinking and writing the world, to be a kind of scenography for the care of friends. It speaks from auto-didacticism, and it speaks of luminosity (positioned distinctly from enlightenment) as a way to renew our thinking about the world of the animate, and the far most world of the inanimate. It proposes an awareness without masters, and an openness to a plurality of cosmologies that we have inherited, and which we must keep inventing.

You are practising artists who have been actively curating, beginning with “On Difference #2” in Stuttgart, followed by “The Rest of Now” at Manifesta 7 (2008) and Shanghai Biennale (2016), among others. How would you describe the interplay between your art practice and curation?

You rightly point out the long path that our curatorial practice has taken. Our participation with Building Sight in “On Difference” at Kunstverein Stuttgart was in 2006. It worked for a new understanding of cities emerging from the extended work that we were activating in and around Sarai, and also drawing from our conversations within the documentary film world. And since then, pretty much every two years, we have embarked on a disparate range of curatorial practices of varying dimensions, scales, and duration, in Delhi (Sarai Reader 09, 2012-13, Insert2014, and the ongoing Five Million Incidents) and elsewhere (Manifesta 2008, Shanghai 2016, MACBA Barcelona 2018, and the ongoing Yokohama Triennale).

Thinking through this timeline, we can feel a kind of contrapuntal rhythm that has organically established itself between our art practice and our curatorial practice. Since Sarai (initiated in 2000 at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi) we have been arguing and experimenting with an infrastructural mode of practice. This was to keep questioning the boundary conditions of knowledge and of art, and shifting the protocols and thresholds of entry, and the dialects of participation. Our curatorial practice has become an intense site of furthering this questioning, and a commitment to its implications. On the other hand, our artistic practice has delved into finding ways to narrate, to unearth shifting narratives of place and time, multiplying perspectives, and re-ordering foregrounds — and to do this with a fictive play and charge of images, objects, and words. These tendencies parse and draw in riddles, tales, landscapes, devices, maps, figures, and encounters.

One terrain that we see our artistic and curatorial work interlace is around the idea of the gathering. In our artistic practice, we have experimented with many forms of crowds and thickets. This we bring to our curatorial practice, and have invigorated processes and artistic play. For the opening event for the Yokohama Triennale, we had an online walkthrough with Eriko Kimura, member of the curatorial team for the YT, for all our artists and their friends. This was a never-before form: Eriko-san walking and conversing, and we three, from our respective homes, narrating the ideas and meetings that made this crossing possible. It lasted two and half hours. After this we had a virtual gathering with the artists for more than four hours. Almost 30 of us talked and listened, some drank, all laughed, and one slept. Distant places of the world came together. It has been a unique experience of witnessing an emergence of a new world, a reformulation of time into what some are calling the new-normal.

Urban research has been one of your major areas of interest, from Growing Up (1995) to The Wherehouse (2004), 5 Pieces of Evidence (2003) or Log Book Entry Before Storm (2014). If you could discuss these investigations into urbanisation. Does the location where the work is exhibited or based alter the discourse?

A curiosity about the past continuous as much as the present tense of dense habitations of human beings — called cities — is one of the histories of our practice. All three of us are very ‘urban’ creatures, and have been shaped in different ways by the city of Delhi. Its pulses shaped our decade-long work at Sarai where we intersected with a few thousand researchers, writers, coders and programmers, scholars, artists, activists, amateurs, practitioners, and enthusiasts. Furthermore, many of our responses to the city were sharpened by being in companionship to the thinking of the young, working-class writers around the Cybermohalla process.

The urban sensorium is delirious and unpredictable, and it made us take forensic and fabulist directions – as in Five Pieces of Evidence (2003), which was joining the dots between missing persons, data grids, the ‘Monkey Man’, and a hot Delhi summer, or like in Wherehouse (2004), which went towards the drafting of procedures of recounting memories of objects, and the cities that refugees leave behind and yet carry with them. In Log Book Entry Before Storm (2014) we moved further towards the submarine and transoceanic longings of port cities.

More recently, seams of coal and iron in underground mines in remote locations or shipwrecks have called our attention (The Blood of Stars (2016), Pamphilos (2018)). In this lockdown time-zone, out just 2 weeks ago, we have made a short film, a chronicle of the world seen from Delhi, called 31 Days, and we realise that the dynamic between home and world is incredibly complicated and in constant flux, and it changes every day. Within these minor and major fluctuations it is difficult to comprehend what leads to what, but we can definitely say that the sensations felt in Delhi carry, and are mobile, and get thought through in innumerable ways in our art practice.

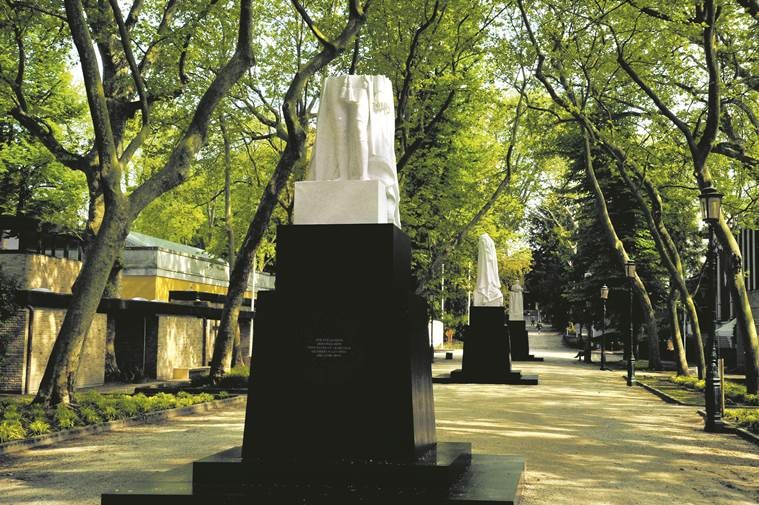

Raqs Media Collective’s 2015 work ‘The Coronation Park’. (Courtesy: Raqs Media Collective)

Raqs Media Collective’s 2015 work ‘The Coronation Park’. (Courtesy: Raqs Media Collective)

If you could talk about questioning racial and historical legacies through your work — from Art in the Age of Collective Intelligence (2015), which discussed the problematic history of wealth displacement to Coronation Park (2015). Even in your curatorial practice there has been emphasis on inclusivity. Also, how would you place the significance of Black Lives Matters protests?

In the preface to his book ‘Fascinating Hindutva’ (2009), Badri Narayan, an anthropologist with remarkable insight on caste mobilisations and transformations, narrates a folktale. He had heard this in village Shahabpur in Uttar Pradesh. This is a luminescent tale about a glorious bird Lalmuni who sings for all, and a troubled king who, on advice from a Swami, wants Lalmuni to sing about him (the king) and narrate all events through him. The king keeps trying, Lalmuni remains unmoved, and the battle is on. The folktale captures, in a marvellous way, the riddle of sovereign power’s eternal trouble with a poet’s heretical flights. The work of artists, of scholars, of all kind of practitioners of speech and images, is somewhere to earn a place in Lalmuni’s world. It is a challenge and a calling, and it cannot be resolved.

When we made the work on the collective murmur of the crowd for the Laumeier Sculpture Park in St. Louis, Missouri (If the World is a Fair Place…, 2015), there was a sense of upheaval to which we were speaking. In the process of making the piece, we invited people to finish the sentence, “If the world was a fair place, then…”. More than 500 responses were collected. In them, the quest for an exuberant collective life was undercut by rage and exasperation. We walked the gardens in 2012, and the work was realised in 2014-15, not long after the Ferguson “riots”, and Ferguson is within extended St Louis precincts. With Black Lives Matter, a long history—which includes the Ferguson events—has (re)appeared with unprecedented force and spread. This has to change the terms by which many institutions and habits work. #Defundthepolice will be critical globally in halting the trend of empowering of police in the face of radical transformation everywhere.

Presently, in many places, many statues are falling. We also have a story to tell about statues. It was through a work called Coronation Park (2015), where we turned the relics of power into ghosts; we took a viceroy out of his robe, made him disappear, and left the robe hanging. We made men of immense power bend. We moved from statue to spectre, from substance to holographic insubstantiality when Coronation Park developed into Hollowgram (2018), a holographic mediation on imperial hubris. To say, like the child before the emperor in the fairly-tale, that the sovereign is naked, and now even without a body! This can produce a strange but potent laughter.

On the other hand, in The Capital of Accumulation (2010), we had cautioned equally against the making of commemorative statues for heretics, as if of the fixing of the spirits of Lalmuni birds. The 20th century is a haunting landscape of statues, and of uprooted statues.

Much of your work requires a certain degree of participation from the audience, from Thicket (2016) to The Great Bare Mat (2013). How crucial is this interaction to your practise or the very process of ideation?

An ethics of conversation and conviviality is something we search for. It is not a given. It is a personal, and a shared pursuit. Since we are a collective, and have further worked at different times with many and different people, it is also a question about the daily and routine process of making, thinking, reflecting. These days, we cannot step into our studio, but that process of conversation continues through a dense intertwining of messaging threads. This process extends outwards, achieving a modicum of clarity, and brings in known and yet-to-be-known people. This is what we think to be the love and excitement for gathering; it weaves publics into a chaotic patchwork. In Thicket (2016), visitors physically wove a web over four days, both physically using lines of blue tape and sonically through acts of reading out loud. In Great Bare Mat (2013) four-cornered discussions, deliberations, and disputes unfolded over a few months at the edges of a carpet woven to echo the meshwork of signals between our three computers and the world on an afternoon in Delhi. We have come to understand that this web, stretching in all directions in space and time, is what makes all of us what we are — a complicated and turbulent combination of debts, risks, voices, and futures.

The curatorial processes in and around Delhi, such as the nine-month long Sarai Reader 09 (Devi Art Foundation, Gurugram, 2012-13) or the ongoing Five Million Incidents process at the Goethe Institut in Delhi (2019-2021), are also instances of this impulse of gathering. These are modalities that we have understood to be of some value to extend the processes that can alter the rules of the conversations and listening. These can provide sustenance for the stamina needed to navigate the contemporary, its many proximities and distances between worlds.

The three of you were active in political action groups during your university days in the ’80s. In an interview, Jeebesh has been quoted as stating that the ’80s was characterised by “the exhaustion of Indian nationalism and a renewal being attempted by various authoritarian voices”. How would define India of now and the notion of “nationalism” in the present?

Recently, an old friend Dudnath, a worker in the Bata shoe factory in Faridabad, passed away. We remembered a conversation from a gathering at his house in January 1990. It was about how we found it possible then to come out of the desolation and despair of the Eighties. In the 80s, we were the generation that saw mega-games, and genocide, in front of our eyes. We saw images of chemical leakage from a factory of everyday ever-readies, of a man in space, of police brutality on minorities and peasants, of the army entering a place of worship, of books being banned, students being killed, temple locks being played out, the slow bitter end to the long strike and extension of AFSPA into Punjab and Kashmir. We also saw the fall of the Berlin wall live and then, shortly after, the fall of an Empire and a war mobilised by a so-called victorious Empire. It shaped us. We are still unpacking its dimensions. We knew something was fundamentally problematic with sovereigns, and the stories the sovereign tells about itself and life under the sign of capitalism — and that many people, especially workers, are also reading and coming to similar conclusions. Our working life started with this recognition.

Now we are in the midst of mass movements and popular reclamation and contestations of public life. Muslim women have articulated new idioms of sorority, and with provocative writings and mobilisations of Dalit-Bahujan thinkers and assemblies, the ground to imagine fraternity afresh has been re-laid. We also see incremental acts of reclaiming time by workers, the refusal of surrendering to debt by farmers, the defence of education by students. There is active concern about incarceration and laws of repression.

The coming times will pose a long-term challenge to the ways in which the structures of everyday life are to be built, sustained, and altered. It will call for more thinking and conversation. Two years ago, during a drive home from a hospital after seeing a friend, the man driving the Uber had contended — ‘Will you be able to let go and move away from this deep-rooted culture of vadh aur bahishkar (vanquishing and banishing) to create anew?’ His invitation was to learn from a more egalitarian ethos available with our cultural reservoir and to make a turn towards unaccustomed terms of engagement.

? The Indian Express is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@indianexpress) and stay updated with the latest headlines

For all the latest Eye News, download Indian Express App.

© The Indian Express (P) Ltd